The ease with which we can disagree on the Middle East conflict, college protests (and everything)

On rational polarization, fanatical certitude, and unintentional gaslighting

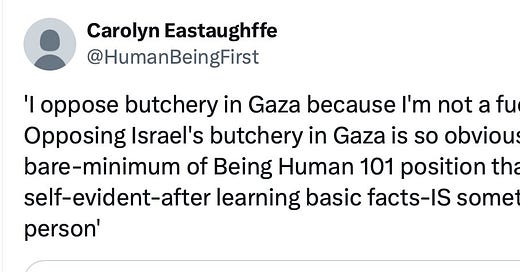

So many people see their takes on contentious issues as “obvious,” as “common sense.” On the Middle East conflict, there are an abundance of takes like these:

There’s an abundance of confident, all-knowing statements everywhere we turn. Protests in support of Palestine are confidently categorized as “antisemitic” or “pro-Hamas” or “absurd.” Israel is confidently described as committing genocide, with insults aimed at people who don’t agree with that framing — while people who have concerns about some protester behaviors are portrayed as entirely unreasonable.

It can often seem like we’re all communally gaslighting each other — unintentionally often, but still, the result is the same.

If there’s a single learning that has led to me seeing the importance of reducing contempt and toxic polarization, it’s this: it’s just so easy for rational, compassionate people to disagree. The more I’ve embraced and explored that as a fundamental law of humanity, the more sense our polarized and angry world has made to me — and the less angry and judgmental I’ve become.

My first book, Defusing American Anger, had a large section where I walked through various contentious issues (e.g., immigration, abortion, race and racism, Trump himself) and tried to help people see how rational and caring people could wind up on the other side of the chasm of our political divides. And my latest book How Contempt Destroys Democracy also does some of that, specifically for a liberal and/or anti-Trump audience.

On rational routes to polarization

Fairly recently I learned about Kevin Dorst, a philosopher who researches and writes about how rational people can arrive at very different and polarized views. He calls this “rational polarization.” He describes his Substack as “A blog about why people are more rational than you think.”

Dorst writes that “we seem to be losing our epistemic empathy: our ability to both (1) be convinced that someone’s opinions are wrong, and yet (2) acknowledge that they might hold those opinions for reasonable reasons.”

And when one fails to recognize how some polarization can be entirely rational, it leads to one acting in ways that amplify the more irrational and dangerous aspects of polarization: undue hate and contempt and fear, unreasonable aggression, and more.

So many data points

The world is very complex; there are so many points of data and so many events happening that we cannot accurately process all of it. We rely on existing stories and stereotypes and shortcuts to help us make sense of all this data and sensory input. We can build different stories based on what tidbits of info we focus on and pull out. And as polarized, opposing narratives coalesce, we’ll be drawn to those dominant narratives — like drops of water rolling downhill and eventually joining one of several dominant channels.

We often focus on the untrue things that our political opponents believe that make them polarized: the fake news, the misinformation, the distorted, biased information. But this misses that we can be polarized by how we filter and parse real and true things.

We are story-makers; we weave stories

And there’s no objective way to parse all this data. Our polarized narratives are often about describing what America and its people are like, or about describing harms being done and what those harms might be like in the future. These are stories; and humans are capable of telling a wide variety of explanatory and predictive stories from the same basic set of facts.

For example, a single murder can be seen as tremendously important, full of meaning about America, or its people, or its institutions — or it could alternatively be seen as fairly meaningless when considering we are a huge nation of 330 million and all sorts of random and unfortunate events will inevitably happen. A murder, after all, is horrible, at one level, and there is undoubtedly meaning of all sorts to be found in it; but at another level, being a single event in a huge world, it has extremely limited meaning. Both of these framings can be true in different ways, and this means that we’ll never align on what “the meaning” really was.

Richard Rorty, in his book Achieving Our Country, made similar points about the pointlessness of trying to arrive at an objective definition of “what America is.” Our conceptions of “what concepts are like” or “what people are like” depend on story-telling — on our wishes and our hopes.

The interpretations we bring to events and behaviors can vary widely, and that’s to be expected. Some might think that this is akin to saying that “truth doesn’t exist,” and that all beliefs are as valid as other beliefs. But that’s not what I’m saying. Truth does exist, but it’s also true that smart, compassionate people can take a large array of true things and weave wildly different stories to explain those truths.

For Middle East conflict, so many truths from which to build narratives

For example, in the context of the Middle East conflict, and the related protests, there are all sorts of true pieces of information that one can use to build various narratives. There are so many events in the history of the Middle East conflict where Israelis and Palestinians have done horrible, violent things to each other; depending on which events you focus on, it’s possible to build an assortment of coherent narratives.

It’s true that Hamas committed horrible atrocities on October 7th; focusing on that can make aggressive war-like responses and collateral damage casualties more justifiable. (If you’re interested in learning more about those points of view, I recommend this post by Isaac Saul, and this post on “bad faith actors” by Guy and Heidi Burgess. This is not an endorsement of their views; these are just resources that helped me understand those views.)

It’s true that Israel has killed tens of thousands of Palestinians and caused a massive humanitarian crisis; a focus on that can make that violence dwarf other considerations. The fact that tens of thousands of people have been killed should make it possible to understand people’s outrage at Israel — even if you disagree and think that view is missing context.

Obviously there is a lot more to say here (to put it lightly). But in short I think it’s possible to see how rational and caring people can reach very different views on these matters (and I can see that even as I have my own views on the matter).

Understanding different views on the protests

For responses to the protests themselves, it’s also possible to see how people are arriving at very different views. It’s true that some Palestine-supporting protesters are behaving in antisemitic and intimidating and unreasonable ways (just as some far-left protesters in 2020 behaved in aggressive and unreasonable ways). It’s true that some activists have expressed support for Hamas. For people concerned about antisemitism and the future of Israel or Jewish people in general, it’s easy to understand why such things are scary. This is especially easy to understand when coupled with worrying trends, like increases in antisemitic acts.

It’s true that some activists’ framings (for example, some oppressor/oppressed framings) can be criticized for being overly simplistic and divisive. (This is not to say that all social power and oppression framings are always faulty; but just to say that some iterations are, in their simplicity, easy to criticize.)

It’s also true that most protesters have behaved peacefully. It’s true that there are Jewish people who attend these protests. It’s true that some people wrongly conflate criticism of Israel with antisemitism (intentionally or unintentionally), and that this conflation can muddy the waters around these issues. (It’s also true that some of the surveys that have been used to paint dire portraits of rampant antisemitism have been criticized as flawed and as overstating the problem.) It should be possible to understand why some people think there’s far too much attention paid to a few bad actors compared to the violence they perceive being committed by Israel.

It’s also easy to see that many people have different interpretations of the slogans being used at these protests. There are some who will claim that “from the river to the sea” is antisemitic, and others who will say it is not. It’s easy to see how people can reach different views on that. Same with “intifada” chants; there are various interpretations about it. At the very least, even if one thinks those slogans are wrong and harmful, one might be willing to cut some of the younger people who use such slogans some slack, as it’s especially easy for younger people to arrive at different or wrong views on such things. (Isaac Saul of Tangle News had a good post in which he explained why he feels that directing a lot of anger at young protesters is unreasonable, even if one believes they’re doing some bad things, because they are, after all, young.)

Part of the problem in these areas, as with polarization in general, is that there is so much stereotyping and flattening of people and their views. Some people who are critical of the protesters are quick to lump in all protesters with the most aggressive and unreasonable ones. Some people who defend the protesters are too quick to act as if all protesters are peaceful and non-problematic and that there’s no understandable reason for people to be upset.

We find ourselves in one of two (or more) divergent realities — and once we’ve embraced that reality we help bolster that reality, using what we can find.

“Fanatical certitude”

In Taylor Dotson’s book The Divide: How Fanatical Certitude Is Destroying Democracy (which I think is one of the best books on American polarization), he writes about our obsession with thinking that we’re in possession of “the truth.” We tend to think that getting people to see the “obvious truth” will result in us no longer needing politics; eventually, we think, we’ll vanquish the ignorant people and we’ll be left with those who see the world in the clearly right ways we do. But this is a pipe dream, as we’ll always find ourselves polarized and at odds about major issues.

And as with so many things polarization-related, there is a self-reinforcing dynamic in these areas. Our views that we’re in possession of “the obvious truth” lead us to become more contemptuous of each other and more polarized — and as we grow more polarized and more angry, we’ll be even less tolerant of people on the “other side” of various issues. The feedback cycle continues.

Towards a less toxic future

People who want to build a less toxic future — a future where we can strongly disagree without contempt — must strive to avoid these pitfalls of collapsing down people and their beliefs into simplistic buckets. They must strive to see what’s bothering people; strive for true empathy and understanding, not just the easy empathy of having empathy for one’s in-group and allies.

Some things you can do

If you liked this post, I recommend signing up for Tangle News; I truly believe that the more people read Tangle News, the less polarized and contemptuous of each other we’d be. You can sign up for Tangle here.

You can listen to a talk I had with Isaac, the founder of Tangle, here:

You might also like this video talk I had with Yakov Hirsch about the importance of embracing cognitive empathy, even for those we might very much dislike and think are doing harm. These are not easy ideas to talk about, but both Yakov and I believe they’re of the utmost importance if we wish to survive much longer as a species — let alone prosper.

Great article, Zach! I have read your first book and are deep into the second De-polarization book. They have changed the way that I talk to people that I disagree with and have a few times that people have shown appreciation for being heard without being attacked. Seems like a bit of a win. Keep up the work! Thanks!