A criticism of “polarization is not the problem” stances

Why American liberals should see polarization as a major problem and want to reduce it

Do you want to better understand polarization and help reduce us-vs-them contempt? Sign up for my free newsletter.

The word polarization refers to a single group splitting into two groups that are in conflict with each other. In the American context, political polarization refers to the divergent worldviews of Republicans and Democrats, and the associated animosity those groups have for each other.

Many believe that polarization is a big problem in America — even our biggest problem. To take a recent example: in early 2023 the former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates was interviewed on Face The Nation and, when asked what the biggest threat to America was, he said polarization. In 2022, political thinker Francis Fukuyama said that polarization “is the single greatest weakness of the United States.”

I think polarization is our biggest problem, not just in America, but for humanity in general. That’s why I devote time to it on my psychology podcast, and why I’ve written a depolarization-aimed book.

But some people argue that polarization is not a major problem in America. A common argument here is that the American conflict is mostly the fault of a single political group, and not, as the word polarization seems to imply, the fault of two groups. People who have this view might use the word asymmetric polarization to communicate that one side is becoming more extreme and unreasonable than the other. Or they may say that the word asymmetric doesn’t go far enough because one group is almost entirely at fault.

Another form of this argument is that we should be polarized: as in, when a country has many people with good ideas and many people with bad ideas, it’s natural that those people will come into conflict, and a good thing they do.

People can use different language to express these objections, especially depending if they’re Republican or Democrat. Still, the underlying argument is the same: our divides are the fault of the “other side” being so bad.

In this piece I’ll criticize some liberal-side “polarization is not the problem” arguments that have recently gotten some attention. One reason I write this is that I haven’t seen much in the way of criticism of these stances. And, because I see polarization as a major problem, I think it’s important to try to get more people to consider this debate.

A couple notes about this piece:

This is a admittedly a rather long piece, but it’s an important topic, so I hope you’ll be willing to devote some time to it.

I am liberal-leaning and I think toxic polarization requires more of us to criticize our own political group. This is something I discuss in my piece How criticizing us-versus-them behavior in one’s political group can help reduce polarization.

Some prominent “polarization is not the problem” arguments

One recent expression of “polarization is not the problem” views was a paper by Shannon McGregor and Daniel Kriess titled A review and provocation: On polarization and platforms. Their argument was that a lot of discussion about polarization doesn’t take into account that, on issues of equality and social justice, liberals are morally correct while conservatives are morally wrong.

As they put it: “struggles against and for justice […] get equated through the lens of polarization.” And clearly it would be a major mistake to equate struggles that are against justice with those that are for justice.

Another proponent of these views is Thomas Zimmer, who often argues that polarization is not the problem, using similar reasoning as McGregor and Kriess. Zimmer communicates his thoughts on Twitter, BlueSky, and his podcast Is This Democracy?. In May of 2023, Zimmer interviewed McGregor (the co-author of the paper just mentioned) and the political researcher Lilliana Mason for an episode titled Polarization is not the problem: It obscures the problem (Apple Podcast link). The following are some statements from a tweet thread Zimmer wrote about that episode:

It’s true that the gap between “Left” and “Right” is very wide, and has been widening. But where that’s the case, it has often been almost entirely a function of conservatives moving sharply to the Right, and the Right being extreme by international standards. […]

One party is dominated by a white reactionary minority that is rapidly radicalizing against democracy and will no longer accept the principle of majoritarian rule; the other thinks democracy and constitutional government should be upheld. That’s not “polarization.” […]

“Polarization” ignores the fact that calls for racial and social justice are inherently de-stabilizing to a system that is built on traditional hierarchies of race, gender, and religion — they are indeed polarizing but, from a democratic perspective, are necessary and good.

Another view they have is that seeing polarization as the problem means wanting people to compromise and “meet in the middle,” no matter how immoral and unjust we see one group’s stances as. In Zimmer’s podcast episode, around the 41-minute mark, Lilliana Mason said the following:

You can compromise on what level of taxation we should have. You can compromise on things like, you know, how much aid we should give to foreign nations. [There are] gradations in those things and you can negotiate and you can find a perfect number right in the middle. […] If you’re talking about numbers, you can find a compromise. Right?

But the problem is when we’re talking about whether an entire group of human beings in the country who are American citizens should be eradicated. There is no compromise position there. We can’t compromise on whether black Americans should be treated equally as white Americans.

What are these stances getting wrong?

What do the arguments from Zimmer, McGregor, and Kriess get wrong? The main way they’re wrong is that they have an extreme bias against conservative points of view and an extreme bias in favor of liberal points of view.

Their arguments show that they don’t understand how it is that rational and well meaning people can very much dislike liberal stances and find those stances to be doing harm in various ways. They seem to view all criticism of and pushback to liberal-side stances on things like Black Lives Matter and transgender issues as entirely unreasonable and as due to hateful or ignorant motives.

They seem to see conservative-side stances on issues of race and social justice as almost entirely motivated by things like racism, or “white backlash,” or a desire to keep “Whites on top of the racial hierarchy,” or wanting to “eradicate” transgender people. They seem to equate the most extreme, hateful conservatives they see with conservatives in general, regardless of how debatable that correlation is.

(If you’re liberal and reading this, there’s a chance you may have some of these same perceptions. And those perceptions may cause you to balk at reading further, because you’ll be angry at me and make assumptions about my goals or views. But if you see our current situation in America as quite bad, I hope you’re willing to continue reading and think about our divides from some different angles.)

The views of conservatives held by Zimmer, McGregor, and Kriess can be seen as being a result of the out-group homogeneity effect, which is a key driver of polarization: we tend to view the “other side” as all the same, which means equating them with the worst people we see in that group. (And this is also of course a dynamic on the right: the most extreme, unreasonable behaviors on the far left affect how conservatives view liberals as a whole.)

One way to see how this view of conservatives is missing a lot is by examining the many thinkers — including politically liberal thinkers, and including members of “marginalized groups” — who have expressed criticisms of liberal-side stances and behaviors they see as unreasonable and divisive (and I’ll list some of those critiques later in this piece). Seeing those arguments present on the liberal side can help us understand how they present in more frustrated and angry ways on the conservative side.

With their bias against conservative-side views, Zimmer, McGregor, and Kriess are unable to see the complexity and nuance in our divides. It will be hard for them to understand how it is that rational, well meaning people can find themselves on the opposite side of the chasm of our divide. And a key point here: we can attempt to understand how those people on the “other side” formed their views while still very much disagreeing with them.

This bias of theirs would make it hard for them to understand, for example, the potential causes of the increase in racial minority support for Trump between 2016 and 2020, and for the GOP more generally — or to understand the significant support Trump had amongst LGBTQ+ voters. With more understanding of the non-bigoted rationale for Republican support, those phenomena are easier to understand (as is Republican support more generally).

At the end of the piece I’ll examine in more detail some specific examples of bias in McGregor and Kriess’s essay. But first, I’ll talk more about what their “polarization is not a problem” stance gets wrong about the nature of our divides at a high level, and what they, relatedly, get wrong about the goals of depolarization-aimed work.

It’s important to define what we mean by “polarization”

When people who want to reduce polarization talk about the problem of polarization, they’re mostly talking about affective polarization, which refers to the high levels of animosity and contempt people in a conflict can have for each other. Polarization researcher Jennifer McCoy and her colleagues refer to this as pernicious polarization: when people don’t just disagree on issues, but have a lot of contempt and hate for the other side (and if you’d like an introduction to these concepts, I’d recommend this podcast episode).

The problem is not simply that our political beliefs are polarized — no one would argue that it’s bad or unexpected to have very different stances on issues. We always have, and always will, greatly disagree on things, and people in both groups will often see the “other side” as doing great harm (and this can be seen as the fundamental challenge of democracy). The real problems arise from the high levels of us-vs-them contempt: that’s when the bad things happen — like election distrust and denial, anti-democratic behavior, and high levels of politically motivated violence.

And the important point there is: our dislike for each other is usually based in distorted ideas we have about the “other side.” We often view the other side much too pessimistically, and fail to see how much we actually have in common. This is one reason affective polarization is also sometimes referred to as false polarization. Much research has shown the various ways in which our views can be distorted: one recent book examining this aspect of our divides is Undue Hate, by Daniel Stone; another is Our Common Bonds, by Matthew Levendusky.

When you have a lot of animosity towards the “other side,” it will become hard to distinguish between polarized beliefs and affective polarization. Or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that your animosity will result in you not having much of a desire to make that distinction. You’ll see the two groups’ animosity as directly linked with their beliefs. On the “other side” you’ll perceive unreasonable and dangerous animosity, and on your side you’ll perceive a morally righteous and necessary animosity.

Zimmer, McGregor, and Ziess seem to have a blindness about the more rational and well meaning motivations conservatives have for their beliefs, and that blindness naturally leads to other blind spots. They’ll find it hard to see that overly pessimistic liberal-side views about conservatives are part of the problem of polarization: that insulting and demeaning liberal-side behaviors contribute to insulting and demeaning conservative-side behaviors.

They think moral scorn and shaming behaviors are warranted, and in this way Zimmer, McGregor, and Ziess contribute to polarization — while at the same time finding it hard to see how they are contributing.

The complexity of us, and our divides

In any big conflict, people on both sides will build their case for why the “other side” has grown more extreme and unreasonable. And one of the things that makes it so easy for both sides to build those narratives is that our world and our conflicts are so complex.

Our political groups themselves are so complex, and so asymmetrical in nature, and our history is long, with so many events, and so many events that can be interpreted in different ways. All this complexity means that people on both sides can easily pick and choose various things to build their case. And their animosity will naturally lead them, without any real effort on their part, to build those narratives.

McGregor, Kriess, Zimmer, and others will make the case that conservatives have grown more extreme and unreasonable. Some people will argue that liberals are the ones who’ve grown more extreme. (If you’d like some information to help you better understand the view that liberals have grown more extreme, I’d recommend this piece by Damon Linker.)

Arriving at the truth of which group is more extreme seems an impossible task: it depends on how one wants to calculate extremity. And even if we could somehow definitively prove that, it would be useless in a practical sense. Much more important than proving “who’s more extreme” is seeing how easy it is for us to form different narratives, depending on which issues and which aspects we or our group choose to focus on. Seeing how easy it is for us to create different worldviews can be, on its own, anger-reducing.

To take one example of group asymmetry that makes our political groups hard to compare: liberal ideas dominate major social institutions, like news media, entertainment, academia, and corporate culture. Also, Democrats consistently win the popular vote. These aspects can help explain some of the belligerence and aggression found on the Republican side: feeling like an aggrieved underdog with “the system” stacked against you can make you more okay with such approaches. It’s possible to imagine an alternate reality where conservative views dominated major cultural institutions in America, and Democrats were more okay with aggressive, insulting Democrat candidates who they saw as necessary to counter that perceived imbalance.

When it comes to liberal views that Republicans have become more extreme, a major focus is on Trump and other Republicans claiming the 2020 election was “rigged.” This is often pointed to as evidence of just how far gone and extreme Republicans have become, and why they’re so much more extreme than liberals. But it’s also possible to see this dynamic as a natural outcome of extreme polarization. For example, after the 2016 election, a survey showed that one-third of Hillary Clinton voters said they didn’t think the election was legitimate. In a 2022 Rasmussen poll, 72% of Democrats said they believed it’s likely the 2016 election outcome was changed by Russian interference. But there’s never been any evidence that Russia influenced the election, or any other strong reason for calling that election illegitimate. (In my book Defusing American Anger, I have a section dedicated to examining the bad logic of election denial on both the conservative and liberal side, and how those behaviors can be seen to feed off each other.)

Another factor here is that it’s not clear how many conservatives genuinely, confidently believe the 2020 election was rigged: many may simply be venting their distrust and frustration, in a similar way that many liberals might have been doing the same in some surveys about the 2016 election (and I examine this nuance in this podcast episode).

This is not to imply that the reactions of both groups or their leaders in regards to elections have been similar. (I myself see no equivalent on the left to Trump’s egregious and prolonged attempt to overturn an election, and I think Trump winning in 2020 would be a very bad thing for America.) This is just to examine how some of the things that bother us the most about the “other side” are somewhat expected outcomes of extreme polarization. And for people worried about worst-case anti-democratic, authoritarian scenarios, this hopefully highlights the importance of reducing our divides, so we can make those worst-case outcomes less likely.

The unhelpfulness of the “blame game”

Let’s imagine for a moment that we somehow knew for a fact that liberals and conservatives were equally at fault for our divides — something it seems impossible to really define, or to know for certain. Even if we were entirely sure that that was the case, we know that extreme division leads to many people in both groups seeing the “other side” as almost entirely to blame. Major conflicts naturally create a situation where the most polarized people on both sides would see the problem as being the “other side” and not a problem of polarization.

In any big conflict, both groups will think the “other side is worse.” And this “blame game” is the primary obstacle to the work of conflict resolution (just as it is in couples counseling). To see polarization as a problem, we don’t have to see the contributions of the groups as equal: all that is required is to see that both groups have contributed in significant ways.

We know that we’ll often have various tribal biases in favor of our group and against the other group, which means we should attempt to embrace some humility about the exact nature of how our divides formed, and how our divides are sustained and how they grow. We should acknowledge that it will always be hard for us to see the precise ways our own group has contributed, or continues to contribute, to our divides.

Even if you’re sure that you’re on the right side in a conflict — as almost everyone in a major conflict tends to be — you might not see how you may be wrong in the ways you interact with others. Our moral certainty can lead us to behave in demeaning, dehumanizing ways to people who have understandable reasons for the things they believe, and this dehumanization amplifies our divides. The 2006 book The Anatomy of Peace: Resolving the Heart of Conflict examines the hidden emotional forces that can help drive conflicts. It explains how people on both sides can contribute, whether in a marital fight or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — and often without even realizing it. When a conflict begins, we might stop seeing the opposing side’s humanity and increasingly see them essentially as objects.

High conflict naturally creates a situation where the people involved will find it hard to clearly see the nature of the situation they’re in. And this is what makes polarization such a ubiquitous and self-reinforcing phenomenon: our social psychology instincts lead us to behave in ways that amplify our divides.

Many people on both sides will expend efforts trying to prove “the other side is worse.” And this is rather pointless: most people’s group allegiences are already well formed, and therefore much of the us-versus-them rhetoric and blaming can be seen as preaching to the choir, or even adding to our divides. The focus on “who’s more extreme” often seems a way for people to justify not having to work on the problem.

Examining liberal-side contributions to our divides

People who say “polarization is not the problem” often avoid examining the arguments about how their political group may be contributing to the conflict. And many people have written about liberal-side contributions to our divides, and this includes many politically liberal people. I’ll review some of these critiques because I think it’s important for more liberals to understand the existence of these critiques. For people who want to truly understand and reduce our divisions, I think it’s important to understand these critiques.

Erica Etelson is politically liberal and in her 2019 book Beyond Contempt: How Liberals Can Communicate Across the Great Divide, she examines insults and disdain aimed at conservatives by liberal politicians and media personalities, and talks about how those insults contribute to our divides. Etelson does a good job of helping you understand the humiliation and anger that conservatives can feel when they experience these insults.

John McWhorter, who is black and a self-described liberal, wrote the book Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America. In that book, he discusses the unreasonable and divisive things he sees on the liberal side on issues of race and racism. He argues that many antiracism activists have a religious-like fury at people who disagree with them, and are unable to civilly engage with different intellectual views. He argues that a lot of antiracism activism actually hurts black people by promoting simplistic framings of complex problems, and presenting obstacles to affecting real, practical change.

The political scientist Mark Lilla, who is liberal, wrote the 2017 book The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics, in which he examines some divisive and unhelpful political approaches by liberals. He argues that liberals too often focus on divisive political activities — like protesting or winning court cases — instead of the harder and more important work of political outreach, persuading others, and putting together coalitions to win elections or pass legislation. He sees liberals’ focus on “identity” as comparable to conservatives’ focus on individualism: both are manifestations of our movement away from more communal ways of thinking and towards more individualistic and selfish ways of seeing the world.

Richard Rorty, who was liberal, is the author of the 1998 book Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America. In that book, he examines how the pessimism and divisiveness of liberal culture, especially academic liberal culture, has alienated people, especially more working-class Americans. His book is well known for predicting that liberal-side approaches might one day soon lead to a belligerent, populist Republican president — which, to many, sounded like a description of Trump.

Skidmore College professor Robert Boyers, who is liberal, wrote the 2019 book The Tyranny of Virtue: Identity, the Academy, and the Hunt for Political Heresies. In that book, he examines unreasonable and divisive ideas and happenings from liberal academia, as he sees them, and gives examples of how those ideas have spread to the broader culture.

Political theorist Francis Fukuyama has written about the divisive approaches of people in both political groups. One thing he writes is that “Many conservatives were not voting for Trump as much as against what they perceived to be a woke extremist Democratic alternative.”

John Wood Jr. is not liberal, but he is someone who spends much of his time working on overcoming our divides. He drew attention to what he saw as an example of polarizing, insulting rhetoric on the liberal-side : the use of the phrase “MAGA Republicans” by President Biden — a phrase which now is often used by many Democrat politicians and activists.

Conflict resolution experts Guy and Heidi Burgess wrote a paper titled Applying Conflict Resolution Insights To The Hyper-Polarized, Society-Wide Conflicts Threatening Liberal Democracies. In that paper, they summarized how people on both sides contribute to our divides. About liberals, they classified the left as divisive in its attempt “to cancel and drive from the public square anyone who has ever expressed the slightest doubt about the merits of any aspect of the progressive agenda.”

I could keep going, but hopefully you get the idea (and if you want links to these books and others about the nature of our divides, see this compilation on my site). If we truly care about a healthier future for America and its citizens, we must be willing to honestly examine how our divides form and how they grow, and this means being willing to consider our and our group’s role in these things.

It’s important to understand what depolarization work is about

McGregor, Kriess, and Zimmer seem to think that seeing polarization as a problem results in a belief that people should “meet in the middle,” no matter the badness or unjustness perceived in the other group’s stances. They seem to think that depolarization work is about compromise for the sake of compromise: that the goal is “unity over everything else.”

In their essay, they say:

Not all extremism, incivility, and/or toxicity is created equal. […] Much of the literature frames pro- and anti-democratic performances of political identities, deployment of moral language, and unwillingness to seek compromise as equally bad, as if we should equate Black Lives Matter and Stop the Steal.

In Zimmer’s podcast episode, Lilliana Mason summarizes this kind of view, saying, “The problem is when we’re talking about whether an entire group of human beings in the country who are American citizens should be eradicated. There is no compromise position there. We can’t compromise on whether black Americans should be treated equally as white Americans.”

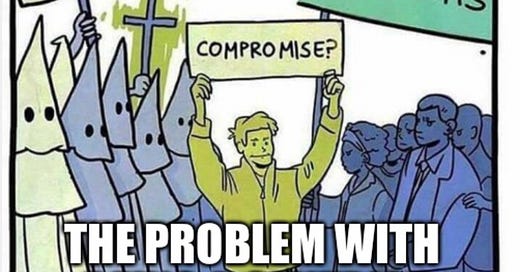

Below is a popular meme amongst liberals who want to denigrate “centrist/moderate” views or the work of depolarization. The views of McGregor, Kriess, and Zimmer seem similar to the sentiments of this meme.

But, from what I’ve seen, people who see polarization as a major problem, and as something we should work to reduce, are not telling people what their views should be, or telling people when or how they should choose to compromise. And even if that were the goal, it would clearly be an impossible one, because politically passionate people will believe what they believe and work towards what they want to work towards.

People who see polarization as a major problem are largely focused on two things:

Correcting our distorted views of each other, and trying to see that we have much less reason to hate each, or be scared of each other, than many of us think. And, as a result of that, we’ll be more likely to see the many values and beliefs we do have in common: our areas of common ground.

Changing how we engage with our political opponents, even as we continue to very much disagree with them and work towards our political goals. And part of that work means seeing the ways in which our ways of engaging with our “enemies” may be contributing to our divides, and to the very things we’re angry about.

The real question: do you want to help reduce the toxicity of our divides?

For the reasons I’ve elaborated, I argue that you can believe that the “other side” is much worse while still seeing polarization as a major problem. All that is required to see polarization as a major problem is seeing that there are ways both groups have significantly contributed to ramping up animosity and, as a result, that there are many things people in both groups to work on.

If you can see that both sides do contribute, maybe you can also see that the only way we get better is for more people on both sides to work on the problem, even if they think the other side is worse. Because we won’t get out of this by simply pointing fingers and righteously judging the “other side.” The other side will not listen to us. But we can have influence on our side.

Regardless of how you define the problem, or the language you use, I think the most important and practically useful question is: Do you want to reduce the toxicity of our divides, or not?

Do you want to take more de-ecalating, depolarizing approaches, even as you work towards your political goals? Or do you want things to keep going as they’ve been going, with both groups being driven into more and more divergent realities and, in the process, becoming increasingly angry and hateful?

The most dangerous manifestations of polarization — election denial, undemocratic behaviors, and other behaviors that threaten our democracy and our stability — arise from our extreme us-versus-them animosity. If you’re someone concerned about those worst-case outcomes, you should very much want to understand, and reduce, our divides, because that is how we avoid those worst-case outcomes. And seeing the problem clearly means being willing to question your biases and unflinchingly examine your and your group’s role in the equation of our divides.

If you enjoyed some of the ideas in this piece, I hope you’ll listen to my podcast, or check out my book Defusing American Anger. If this essay raised questions for you, many of those questions are probably addressed in my book, or in my podcast.

Examining bias and bad thinking in McGregor and Kriess’s essay

This concludes the main points in this piece but if you want to read some analysis of the bias in McGregor and Kriess’s essay, keep reading.

I’ll start with something they write at the end of their essay, as I think it highlights the subjective nature of many of their arguments. They write that:

Rather than read ‘Fuck Your Feelings’ as an apolitical expression of political negative affect — which is exactly what polarization scholars would focus on — we should understand it as a very real statement of political interest; namely, keeping Whites on top of the racial hierarchy.

This seems to be an extreme case of mind-reading: they confidently claim to know what’s in the minds of people who use that phrase, while also taking the worst-possible interpretation possible. There are clearly many ways one can interpret the “fuck your feelings” phrase: one more-generous interpretation is that it’s an expression of frustration resulting from a perception that liberals too often value their own subjective experiences over things like facts and statistics. It can also be seen as a general way to insult an opponent who one sees as non-rational and overly emotional: for that reason, it’s easy to see how it can be used by anyone who wants to denigrate a political opponent, and easy to see why liberals sometimes also use it. (For more thoughts about this phrase, I’d recommend this Quora post, which includes responses from liberals and conservatives, or the responses to this tweet of mine.)

McGregor’s and Kriess’s bias is evident at the beginning of the essay, also. In the first paragraph, they use the word “murder” when describing the death of Michael Brown, who died from being shot by police officer Darren Wilson. But Wilson was never found guilty of a criminal act, despite several investigations, and this seems to be largely because there were eyewitness accounts that Michael Brown was in the process of running back towards the officer after he’d previously fought with the officer and tried to take his gun. The use of the word “murder” quickly establishes that we’re more in the realm of political activism than in the realm of objective academic work. (For liberal people who are interested in learning some of the views that inform the more conservative-side view of that incident, I recommend the documentary What Killed Michael Brown?. If you genuinely care about reducing our toxic divides, it’s important to be willing to examine different views to understand how those views can be held by rational and well meaning people, even as you may also disagree with those views.)

McGregor and Kriess’s essay focuses on George Floyd and the reactions to his death, and paints conservative-side responses to George-Floyd-related activism as largely motivated by bigotry and a lack of compassion. The paper says that that incident “provoked intense White ‘backlash’ in the United States and beyond.” It says that “Alongside the rise of Black Lives Matter, since 2014, ‘thin blue line’ flags — symbols of solidarity with White police forces — began to grace Facebook pages, show up at Trump and Republican rallies and the Charlottesville ‘Unite the Right’ rally, and fly on porches across White America.”

But conservative-associated responses to George-Floyd-related activism and protests and riots, and to BLM, don’t require bigotry or racism. It’s possible for rational people to believe that George Floyd’s death was not obviously caused by or related to racism, and that it did not tell us anything significant about racism in America. One reason people can believe that is because white people have died in similar circumstances while in police custody. Another aspect of this is that a significant number of white people are killed by police, and those deaths don’t gather much attention or examination. To many people, the racial imbalances in killings by police can be explained mainly by higher rates of policing of higher-crime neighborhoods, and therefore more interactions happening in areas that contain more racial minorities. And this can be seen as a complex problem: for one thing, many people in high-crime areas, understandably desire significant police presence.

When seeing things from that vantage point, it should be possible to see why it is that some people think that liberal-side responses to George Floyd’s death were unreasonable, divisive, and dangerous. And, because this is an important point for depolarization purposes: it should be possible for people to understand those beliefs even while also disagreeing with those beliefs. Understanding does not equal agreement.

I myself do not agree with the Black Lives Matter movement or approach. This is not because I disagree with the literal meaning of the phrase but because I disagree with its generally understood meaning: I don’t think that racism is a significant factor in killings by police. I think our high rate of police killings is caused mostly by America’s huge number of guns, and I think a lot of liberal-side approaches on the police violence topic have been counterproductive and unnecessarily divisive.

The political scientist Mark Lilla is politically liberal. In his book The Once and Future Liberal, he agrees with the goals of BLM but criticizes the movement for its divisive tactics:

Black Lives Matter is a textbook example of how not to build solidarity. There is no denying that by publicizing and protesting police mistreatment of African-Americans the movement mobilized supporters and delivered a wake-up call to every American with a conscience. But there is also no denying that the movement’s decision to use this mistreatment to build a general indictment of American society, and its law enforcement institutions, and to use Mau-Mau tactics to put down dissent and demand a confession of sins and public penitence (most spectacularly in a public confrontation with Hillary Clinton, of all people), played into the hands of the Republican right.

If you can see how even liberals/Democrats can be bothered by such things, it should be possible to see how it is that conservative people, with their pre-existing frustrations with Democrats, and biases against them, can view such things through an even more pessimistic and anxious lens.

In their essay, McGregor and Kriess quote from another paper that said:

We find that opposition to Black Lives Matter is not driven by the idea that all lives matter equally; instead, it is driven by the belief that non-Black lives should matter more than the lives of African Americans.

In this framing, there seems to be no room for reasonable, non-racist objections to BLM or its approaches. Conservative-side stances on this topic are simply bad and racist. (These arguments can be constructed by finding a correlation between survey results interpreted as racist and pushback against liberal-side stances. This framing can be criticized though, because even if there’s a correlation present, it does not explain the beliefs of everyone on that side of an argument.)

People who see only racist and bigoted motivations for conservative-side stances will fail to understand the complexities of our divides. Even worse, their simplistic good-versus-bad framings will amplify our divides by creating more animosity and righteous judgments.

Let’s take transgender issues. Their essay also portrays any pushback to liberal-side ideas in that area as representing injustice. They say:

It would be wrong to equate anti-democratic extremism, for instance, with movements for gender, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, queer/questioning, intersex, and allied/asexual/aromantic/agender (LGBTQIA)+ and racial equality that are fundamentally about creating political equality for social groups, even if these movements are at ‘extreme’ poles.

But again, this misses that there can be rational and well meaning objections that people — including some liberal people, and including some transgender people — can have in this area. As with their other arguments, it sees conservative stances as being represented by the most hateful, most extreme people on that side of the argument. This view of things fails to examine the nuance in this area: for example, the fact that a significant percentage of Democrats agreed with the language in the Florida legislation known as the “Don’t say gay” bill. (If you’d like to better understand some of the more rational conservative-side arguments in this area, I’d recommend this podcast episode of mine.)

And again, because this is such an important point for depolarization work: you can attempt to understand why people on the “other side” believe what they believe while disagreeing with those beliefs.

From a broader level, we can see Kriess and McGregor’s paper as representative of a major bias in academic work in general. We can see how there are many academics who spend time attempting to communicate their polarized views and biases using academic language, and referencing studies by other academics who have done similar things. This can lend a veneer of objectivity and intellectualism to what are often simply works aimed at making the point: “See how bad these people are?”

To take one example: there’s a lot of academic work that seems devoted to finding evidence of a high level of racism amongst American citizens. As someone who has looked into that academic work, I’ve found that many of those framings are based on subjective studies and interpretations that can be criticized in many ways: this is something I examined in another podcast episode of mine.

For politically liberal people who care about reducing the toxicity of our divides, part of that work will mean being willing to examine the bias in liberal-side academic work, and being willing to push back on those framings when you think they’re unhelpful and divisive. For more on that topic, I recommend this podcast episode about how liberal bias amongst academics and conflict resolution professionals can impede depolarization work.

Wanted to say thanks to David Foster and Molly Elwood for giving me feedback and comments on this piece.

Thanks for this piece. I am a psychologist and Jungian analyst who works with couples and adult pairs to break through polarization. We use the term “projective identification” to talk about the emotional entanglement of assuming that you know someone else’s intentions and feelings (without asking them) — meaning you attribute their motives to them. All humans have strong emotional needs to control others in order to get their own needs met. This kind of interaction begins in infancy before we have words, but then after we have language, we lay the words on top of the emotions and we criticize, attack, destroy, defeat and even kill others because we believe “they” need to be controlled. “We” are morally superior. Moral superiority is one of the biggest problems for human beings and it’s connected to politics, opinions, religion and now has been connected to “calling-out culture” that ruins people on the internet. Cognitive science has demonstrated that humans are about 95% unconscious most of the time. Have a look at Kathryn Schulz’s book “Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margins of Error” and you will see that people are wrong about what they saw, heard, and remember a majority of the time. So in addition to the hatred and enmity that is generated by polarization, it generates a lot of errors and mistakes and truly dehumanizing views of other people. The only possibility of true problem-solving once polarization has gotten going, and there is defensiveness, moral superiority and mistake-making all around, is to gain an ability to lower emotional threat and work with one’s own seeing/hearing/feeling. At the Center for Real Dialogue (www.realdialogue.org), a new non-profit start-up where I am Executive Director, we are assembling a wide array of courses to teach the Skill of Real Dialogue which is Speaking for Yourself, Listening Mindfully, and Remaining Curious. We also teach about learning from our defeats and failures and remaining modest about what we know because we are often wrong. Political differences are often a matter of style, level of development, and family or other influences. There will never be just one side that is correct because of the nature of being human: we are often wrong, we like to control each other, and we can see only a narrow range of any reality as individuals. We need each other to solve our problems. We need to speak and listen mindfully in order to work with our own minds, especially once conflicts get going. There’s a long road to reckoning with how wrong we are and I appreciate your work, Zach, in trying to wake up the liberals to their one-sidedness. We need both sides of all human perspectives because we so one-sided, by our nature.

You know, this post really helped open my mind...

I had previously been locked into a lot of ways of black-and-white thinking around certain subjects. Even after openly dissenting, there's still a passive voice in the back of my head telling me I have to follow the views of the side I used to belong to. Take police violence, I assumed I could only see it revolving around race, everything tied back to race, and the only different takes on it would be different race-related solutions coming from anti-racism activists who disapproved of the most commonly seen tactics. I never thought to consider guns as even a part of it.

Or, in general, looking at all the moving parts of society as a whole, and how different practical solutions may affect them. All I knew for years was "identity politics."

As a conservative, I'm happy to find we have a lot of common ground! Thank you for sharing this piece.