Can we break out of the self-reinforcing polarization "doom loop"?

To avoid destruction, we must own our own role in toxic polarization

I shopped this op-ed around last week but wasn’t able to get it placed; was too short a time window I think. It’s my attempt to persuade Americans why they should see it as vitally important to work on reducing political toxicity, even as they may be very angry and scared post-election. I think it’s a strong and succinct summary of the argument but I’m curious to hear your thoughts: what would you change?

For an audio version of this piece, go here.

No matter who wins the election, we’ll likely see toxic political polarization get worse, at least for a time. Post-election we might see various powderkeg situations, involving militant protesters and counter-protesters, anger-amplifying legal battles, constitutional crises, and who knows what else.

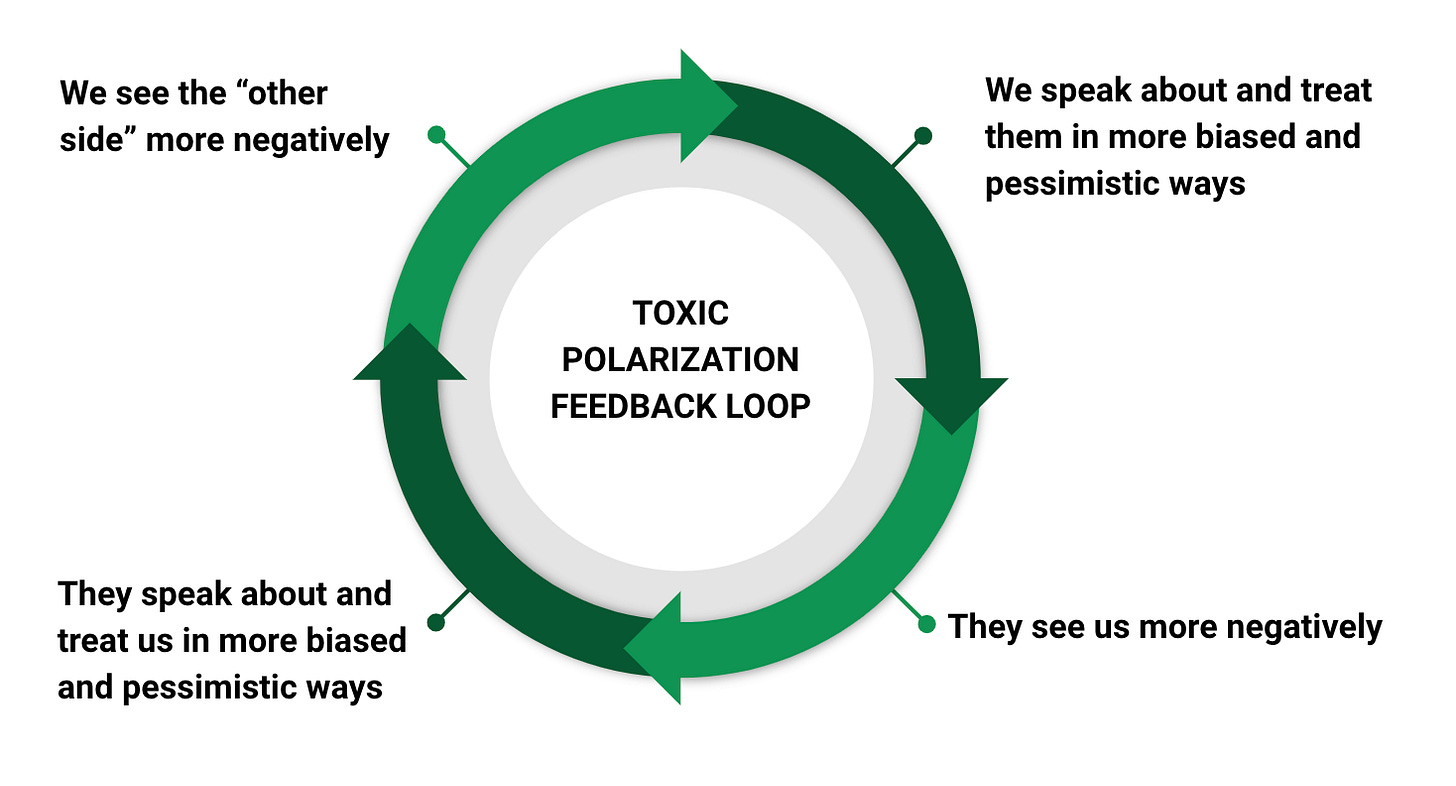

To avoid us tearing ourselves apart, we need more Americans to see that we’re caught in a feedback loop of conflict. Each group’s contempt and fear provoke contempt and fear from the “other side,” in a self-reinforcing cycle. Political scientist Lee Drutman refers to this as the “doom loop.”

A common objection to that framing, made by people in both political groups, is, “Polarization implies both groups are at fault, but this is all the other side’s fault.”

But we must see that being in conflict makes it hard for us to see the nature of that conflict clearly. We’ll often fail to see how “our side” has contributed.

Many on the left speak as if our divides are entirely Trump’s fault, or entirely Republicans’ fault. Ezra Klein’s book Why We’re Polarized was influential in making the case for this view of our divides. But that framing ignores the fact that entire papers and books have been written by liberal-leaning people about the ways in which liberals have contributed to our divides.

For example, there’s Musa Al-Gharbi’s paper “Race and the race for the White House,” in which he criticizes some popular books and studies for overstating racism and authoritarianism as key motives in support for Trump. There’s Erica Etelson’s book Beyond Contempt, which examines insulting liberal-side rhetoric that has amplified toxicity.

On the right, many speak as if all the fault lies with liberals. This is despite the obviously conflict-amplifying nature of Trump, among other divisive and belligerent figures on the right.

Many feel that admitting both groups play a role is akin to saying, “Both groups are the same.” But that’s wrong. One can think the “other side” is much more toxic while seeing the importance of reducing hostility. We can’t let anger and blame be excuses to avoid working on this problem.

Another conflict-amplifying tendency many of us have is making faulty comparisons between “us” and “them.” Republicans and Democrats are not like the two sides in a chess game, with the exact same pieces and rules. Human groups in conflict always have different traits and motivations; the groups are asymmetrical.

For example, in America, liberal-leaning people control powerful cultural institutions, like the news and entertainment media, and academia. This asymmetry can explain why Republicans feel like underdogs fighting a powerful establishment, which can be one factor to help explain why they condone more belligerent approaches.

Other asymmetries are present, like those related to class, education, and religion, to name a few.

This helps explain how people can build narratives where “it’s all the other side’s fault.” Democrats, for example, will focus on the uniquely belligerent nature of Trump. The fact that there’s no Democratic version of Trump will be seen as strong evidence that “it’s all their fault” — that there’s nothing Democrats need to work on.

Republicans will focus on Democrat-side stances they see as having grown more extreme; for example, the rapid increase in pro-immigration stances among Democrats, or the spike in support for anti-police ideas in 2020, or the radicalism they perceive on college campuses.

People on both sides will filter for things that “they do” but that “we don’t do” to arrive at defensible arguments that it’s the “other side” that has grown more extreme and dangerous.

We also fail to see that our perceptions of our adversaries’ badness and extremity can result in our own stances growing more extreme and polarized. Conflict can be like a centrifuge, pushing our ideas away from each other.

Our reactions to our adversaries’ threats will often be seen by them as aggressive provocations. For example, attempts to remove Trump from the ballot were perceived by Trump supporters as evidence that Democrats are the undemocratic ones. (Note that we’re talking perceptions, regardless of whose concerns are more correct or defensible.)

Democrats who see the nature of our conflict clearly must look for ways to lower tensions — which one can do even while working for one’s political goals. Democrats should focus less on Trump’s badness, as they see it, and focus more on why so many Americans are willing to support him. The answer to that lies in the basics of how conflict affects us — how our “undue hate” and exaggerated fears lead us to support and condone aggressive, us-versus-them approaches.

Republicans who see our situation clearly must look for ways to depolarize their party. They must try to make their colleagues see that true leadership and strength isn’t just about “defeating the enemy” (an illusory dream that only amplifies conflict) but about recognizing how conflict deranges and destroys us. True leadership means seeing that toxic, war-clouded mindsets threaten everything we hold dear.

More people should seek to understand their opponents’ perspectives and grievances. For example, Democrats should try to see why many believe Trump has been treated in unfair and irresponsible ways, and how that’s a large factor in his support. They should also see that a lot of his support is due to people strongly disliking Democrat-associated ideas, and not simply because they’re enthusiastic about Trump.

Pro-Trump people should seek to understand why so many see Trump as divisive and dangerous. If they want others to take their concerns and grievances seriously, they should be mature and brave enough to try to understand and take seriously their opponents’ fears.

Political leaders who see how our conflict threatens us must try to understand the more rational frustrations of their opponents. They must combat insulting and dehumanizing views of the “other side,” both within themselves and among their peers.

We of course can’t entirely avoid angering each other as we pursue our vision of what’s right. The perceived stakes are high, as are our emotions. But with a more clear vision of American polarization, political operators will be in a better position to reduce the corrosive effects of hate and pessimism.

History will look kindly on those wise enough to work on this problem — especially because these efforts take true bravery and strength.

Will we be able to avoid worst-case scenarios of dysfunction and chaos? We all have a role to play in what happens next.

Zachary Elwood is the author of “Defusing American Anger.” He hosts the psychology podcast People Who Read People.

This is a wonderful article and I’m glad it came up on my feed.

Yikes, just found this article as Trump's EOs are sending Dems off the far left cliff. Thank you for the inspiring thoughts.